This Utopia Does Not Exist: My talk @ MIT

Against Platforms / For Intra-Institutional Technology

I’ve been working on the next chapter of Against Platforms since its publication. One of the book’s arguments is that our solution to the problem of platforms must be to reformat the institutional form. Most of my work since then has been to fine-tune what I mean by this—starting with the work of thinking about what would constitute a useful new institution and why. This summer, I was invited to give a talk about Against Platforms by MIT Radius. I’d partially imagined this book serving as an intervention for technologists who had not previously been exposed to the critiques in the 21st century. I used this talk as an opportunity to outline a practical guide for institution building. This is an evolution of remarks I gave to Rhizome World, and regular readers will notice I’ve aggregated from previously-published work. Yet, this is the first time I’ve published my Elements of Technology Criticism on Substack. It’s also the first time I try out my AI Slop Era theory graph. This was compiled as a talk/lecture, so that explains the curt and conversational prose style. I hope you enjoy. Many thanks to the wonderful team at MIT Radius for this opportunity.

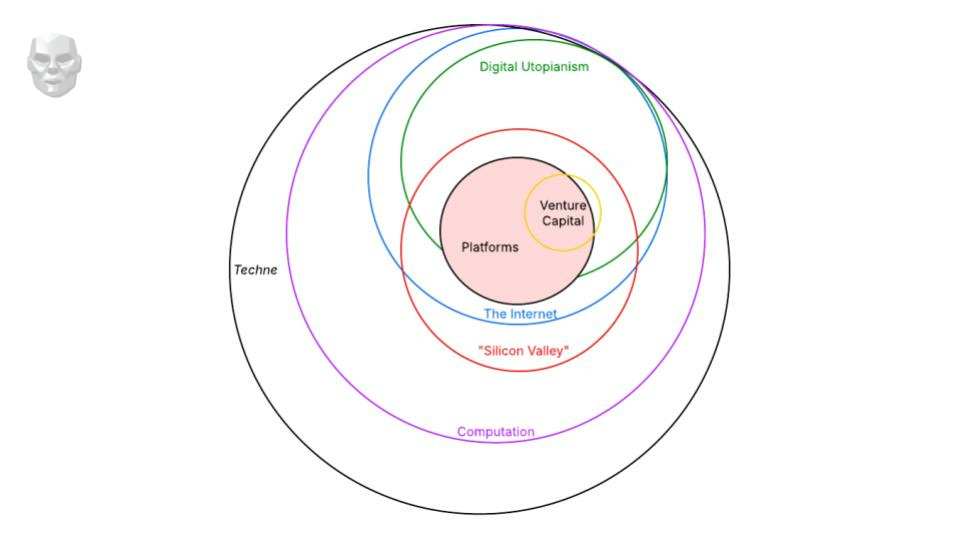

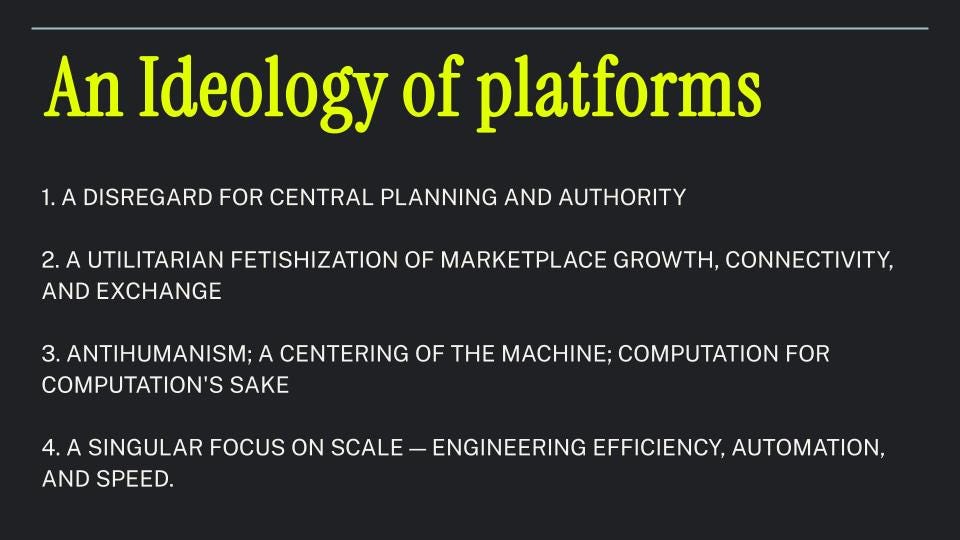

This project begins with the ideology of digital utopianism - the belief that progressive innovations in technology, and technology alone, will create a more egalitarian, democratic society. This ideology is responsible for some of the most pivotal economic and political developments in the first two decades of the 21st century. The rise of personal computing, mobile devices, social networks, and low-interest rate-fueled venture investments formed what theorists have called “platform capitalism.” Other than the physical technology and infrastructures that make it work, what accounts for the rapid rise of this new power center? Surely, the power of Silicon Valley is not simply a feat of superior engineering.

What makes digital utopianism different than other kinds of utopianisms is its disregard for our existing political, social, and cultural institutions. This rather abstract development is referenced constantly under the rubric of so-called disruption. Disruption generally refers to Clayton Christensen’s “disruptive innovation” that targeted large, incumbent corporations. I’m talking about the kind of silicon valley utopian who wants to remove our most essential institutional structures. In their place, this digital utopian prefers digital platforms. And this is what makes digital utopianism so elusive - it’s a worldview where political institutions lose their basic connection to the public. My core argument is that the route towards combatting this ideology is not to reform or amend its aims, or actions, but to fundamentally re-constitute the role that institutions and institution building might play in the coming digital economy.

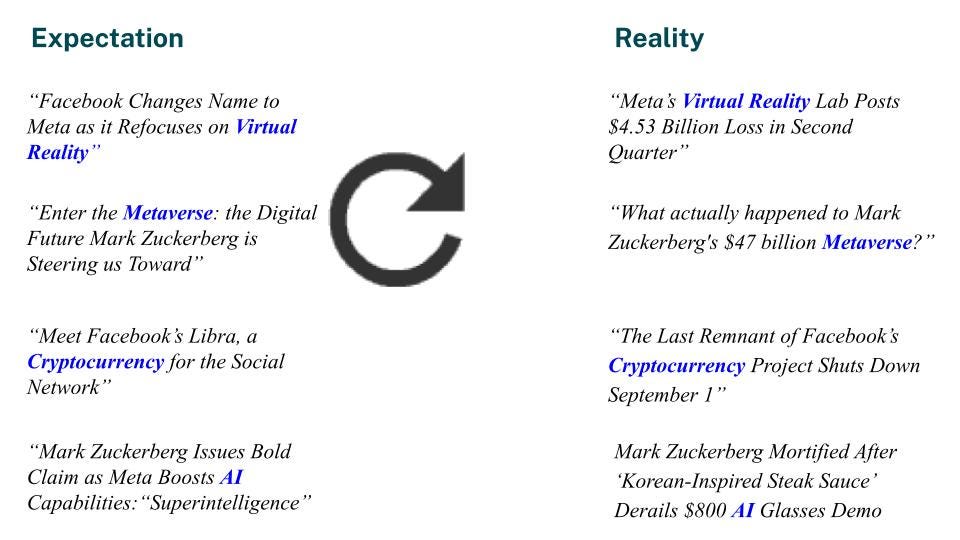

We’re not starting from scratch. In the last decade plus, we have seen a backlash to the exploitative power of digital platforms. This includes critical literature dissecting its effects, a new type of journalism holding these platforms to account, and a popular revolt against its forms of control. We know today that the dream of digital utopians was a mirage. The cyberspace where corporations and states have no stronghold was but a fiction, and the digital networks we have erected instead enable them historically unprecedented levels of command and control. The platform owners told us they were tearing down gatekeepers, but instead chose profit.

My work meets this critical reaction midway. Still, I found that something is missing. How and why did our institutions of small l liberalism fail to contain such a consolidation of power?

If today’s predicament is any measure, the checks on this power badly need reform. In the 2010s, we saw the dark side of private-sector ‘disruption.’ In the 2020s, we’re seeing what happens when Silicon Valley platforms gain the kind of power once reserved for the state.

But too often what we call “technology criticism” has resorted to lazy dystopia. The future problems are more mundane in both their causes and the ways they will be carried out. Plus, you will not get very far trying to persuade a utopian that they are building dystopia. As we know from Thomas More, utopia is “nowhere” to be found. Dystopia, too, is an illusion that effective critics would be foolish to follow.

The focus of our criticism must be on the root ideology and its connection to power.

If you persuade people how and why a specific ideology takes hold, and what the stakes are for its proliferation, you have done much more work than simply attacking a specific, local formation.

Imagine the metaphor of a mythical hydra in battle. If you just cut off one limb, you will still have to deal with the others. Killing off Theranos, exposing charlatans like WeWork founder Adam Neumann, and investigating the fraud underlying FTX will not stop these kinds of things from popping up again. Some of the greatest achievements of the 2010s tech lash have done little to slow down newer forms of the same.

How many techno-utopias have to fail before we learn to apply some scrutiny?

Instead, we must focus on the neck that connects the many limbs to the head - the site of the ideology that controls the entire beast.

How can we distill Silicon Valley’s ideology to its core elements, separating the apparatus of “technology” from the broader worldview?

The outline for this book started as a list I published on my website. I called it The Elements of Technology Criticism.

It was my attempt to synthesize the emerging field of technology criticism into a set of recurring general principles.

It was a diagnostic of the folly of Silicon Valley’s hubris after it had been laid bare. But it is also a forward-looking taxonomic guide to the ideology of platform capitalism’ most essential contradictions. One of the core tenets of The Elements was to make visible what has always been purposefully obscured, to bust the myths that were increasingly accepted as conventional wisdom.

But what made it most potent was the post’s utility as a blueprint for political action. I hoped that those who built things with technology would be able to recognize the hidden contradictions that have led us to the current ideological impasse.

When an ideology becomes overpowering, the first act of resistance is to name its components, to make them visible. This starts the work of unseating an ideology from its silent power.

The 14 elements of technology criticism

Data is never “raw,” immanent, or neutral. There is always bias and distortion in capture and modeling.

The internet is not “a thing.” It is a distributed network of many layers. Treating it as its own monolith with a central cultural logic presents problems.

Technology can never occupy a space outside of capitalism. With rare exceptions, every application, company, or innovation will have a funding source, a board, and a bottom-line; and in all cases the logic of capitalism will eventually supersede and control technical tools. Too often, what we identify as “tech” is just capitalism, but faster and worse.

You can’t solve a social problem with a technical solution. Applying technical fixes only treat the symptom, and, in failing to address the underlying cause of the problem, makes it worse.

If you are not paying for a platform, your data is the product. Attention is data and data is a commodity. If something is free and connected to a network, beware of the tradeoffs.

Decentralization is an illusion. Even distributed networks enforce hierarchies of power and influence.

Software is hard. Computing interfaces, rules, interactions, and protocols encode certain behaviors, and for that they should be scrutinized and interrogated as part of the body politic and the built environment.

Algorithms are made of people. They are editors, they steer and privilege certain values, and are never objective.

Beware of “open access.” Information may want to be free but somewhere a new gatekeeper will benefit.

Once a measure becomes a target it ceases to become a measure (Goodhart’s Law revisited). optimizing for a goal in a closed system will reinforce the production of that goal, and cease to deliver any insights.

Information is the enemy of narrative. The more information, the more doubtful the narrative becomes.

Crowdsourcing is a race to the bottom. Labor, knowledge, education, etc.. are all cheapened when forced to compete on a platform. Making it easier to perform a task has massive externalities.

Your brain is not a computer and your computer is not a brain. There are things that cannot be automated, and intelligences that machines cannot have.

And finally, Platforms are not institutions. Do not confuse them.

How did we get here?

I offer two arguments about today’s particular brand of digital utopianism and its platform formations.

Is it not native to technology, nor even computing, nor even digital media. All of those things exist alongside it but are not totally contained by digital utopianism. For example, there are software, hardware, and even AI tools that don’t spring forth from nor re-create the world in the image of the digital utopian.

Today’s digital utopian has morphed into a kind of self-fullfilling prophet whose chief target is not the absences of technical progress, but instead the form of the institution. As Elon Musk’s now all but mothballed DC based skunkworks project DOGE has shown, the end goal is less efficiency than it is the destruction of any institutional political boundaries that might create constraints to the scaling powers of computation.

We’ll get back to Institutions later, but first, I want to talk about how we arrived at the contemporary form of digital utopianism, and what that has to do with platforms.

So if we agree that, for now, Technology and Silicon Valley are connected yet distinct formations, here is my simple intellectual patchwork diagram of how we have somehow arrived at Silicon Valley 2025 - the Silicon Valley of DOGE (the Department of Government Efficiency) and the alliance with Trump’s MAGA movement.

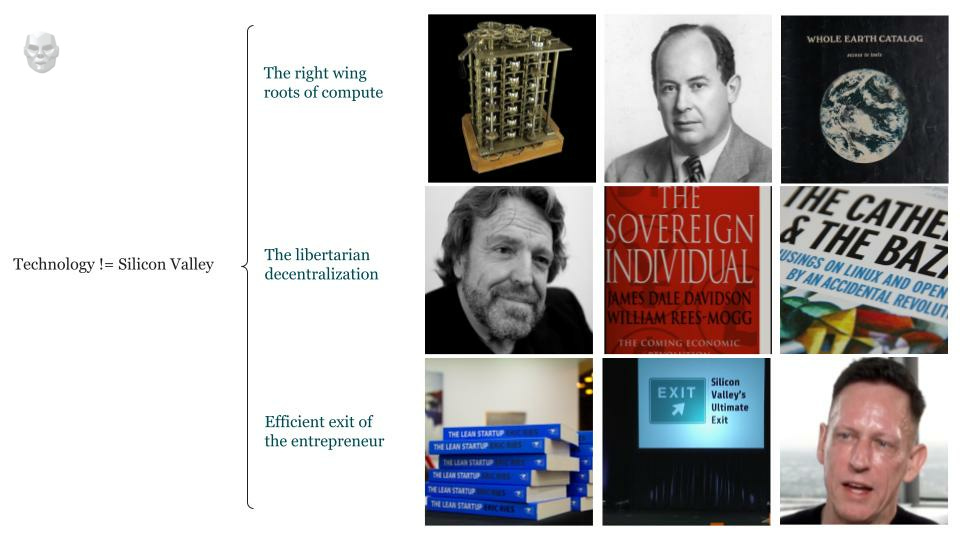

We begin with the right wing foundations of computation1:

Charles Babbage’s Difference engine was formulated on theories of labor discipline. This was a reflection of Babbage’s belief that the highest ambition of the plantation manager was to reduce the skill and cognitive complexity of a worker’s tasks. From its earliest days, computing’s intent has been to shrink human involvement in the administration of multi-faceted instructions. Already off to a rough start.

A few generations later, the father of Cybernetics came to a different conclusion. Norbert Wiener warned about the dangers of automation, and advocated for democratic control of the rising power of cybernetic control. James Barbrook details in his wonderful book Imaginary Futures how Weiner’s “left wing” cybernetics would be defeated by John Von Neumann’s “right wing” vision of cybernetics, one perfectly aligned with Cold War imperatives of the time. Norbert Wiener’s idea that cybernetic “feedback” could improve human institutions was replaced by Von Neumann capitalist interpretation: if computers could become thinking machines, then artificial intelligence research could eventually replace humans, and labor. Corporations were interested.

It wasn’t long until the hippies joined the party.

The “Whole Earth Catalogue”, published by Stewart Brand inspired a loose grouping of new communalists who formed a techno-centric revolution against the authoritarian Cold War state. “Information wants to be free”, they said. Free from what? From institutions, which for them was the root of all societal friction.

Enter the Libertarians. This came to a head with John Perry Barlow’s “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. “Cyberspace does not lie within your” he harangued early attempts at institutional governance of the nascent internet, “do not think you can build it, as though it were a public construction project.”; Barlow is clear: the government, or any human institutions, should steer clear of our new “cybernetic” home of the mind. But whose minds, exactly? The answer was, unsurprisingly, libertarians who distrusted any kind of regulatory checks.

Now allow me one quote from Barlow’s 1996 Declaration:

We are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity.

How soon would we realize that the online world is but a hyperextended mirror of all of our existing biases and censors; that humans behind the servers monitor and manipulate messages on a grand scale? How soon would we discover that access to computation would not be evenly distributed, but in fact would exacerbate the divide between the media rich and media poor.

Then we met the so-called “Sovereign Individuals”, the name of William Rees-Mogg and James Dale Davidson’s best seller from 1996: They promised a future where “the individual will become more of an entrepreneur, a private contractor, in complete control of his finances, with easy access to enormous computing power.” Technology would enable self-starters to reorganize power according to the logic of the private market. No pesky public bodies would meddle in the supreme logic of the digital will.

To get to the real heart of platform ideology, read The Cathedral and The Bazaar, Eric Raymond’s manifesto on building open source software. For Raymond, projects should be distributed bazaars of activity, not cold, planned cathedrals. Cathedrals are “carefully crafted by individual wizards or small bands of mages working in isolation”. This slow, deliberate work is no match for the networked and digitally-enabled bazaar where many software developers move fast by releasing early and often, delegate everything they can, and are open to the point of promiscuity. This veritable bible for computer engineers soon jumped out of the network and into governance of the physical world; most human organizations came to be seen as maligned cathedrals.

Last we have the so-called exit of the entrepreneur

The management method known as the “lean startup” is a lightweight program of data-driven optimizations designed to scale startups. The model prizes efficiency, often ruthlessly so - like Twitter after Musk’s 80% headcount reduction. Instead of human inputs, lean startups use data and algorithms - what they call a test-and-learn approach - to rapidly experiment until the optimal solution is reached. “Lean” startups aren’t just lean in their small size and quick movements - they are part of a related shift from institutional administration to quicker sensing corporate bodies. This philosophy has been applied more broadly in an interrelated move away from democratic governance to a kind of techno-cratic, neoliberal rule of positivist calculation. In “lean society” political institutions need not stand in the way of good data.

Then there is the so-called Silicon Valley exit group represented by Balaji Snrivassan, the founder of the network state movement. It started out as a fringe idea, but today so-called sea-steaders have grown a hyper-libertarian movement among startup founders to exit from the state where decentralized entrepreneurs can work in international waters unencumbered by institutions of government and law.

Then there is Peter Thiel, whose I think needs little introduction in this matter: Nearly everything he has done in his career has been set towards using the power of computation to weaken institutions. Not just academic institutions - he is the founder of the Thiel Fellowship, which offers students $100,000 to skip college to focus on being entrepreneurs. But also social institutions - he was recently asked by a New York Times columnist whether he wanted the human race to endure, and Thiel had to pause before he could answer.

While these thinkers all share the standard fare of digital utopianism (each of their respective eras, technologies, or political interests) what I think is left out of the analysis of them is the way they viewed the work of platforms as leverage against the idea of the public institution.

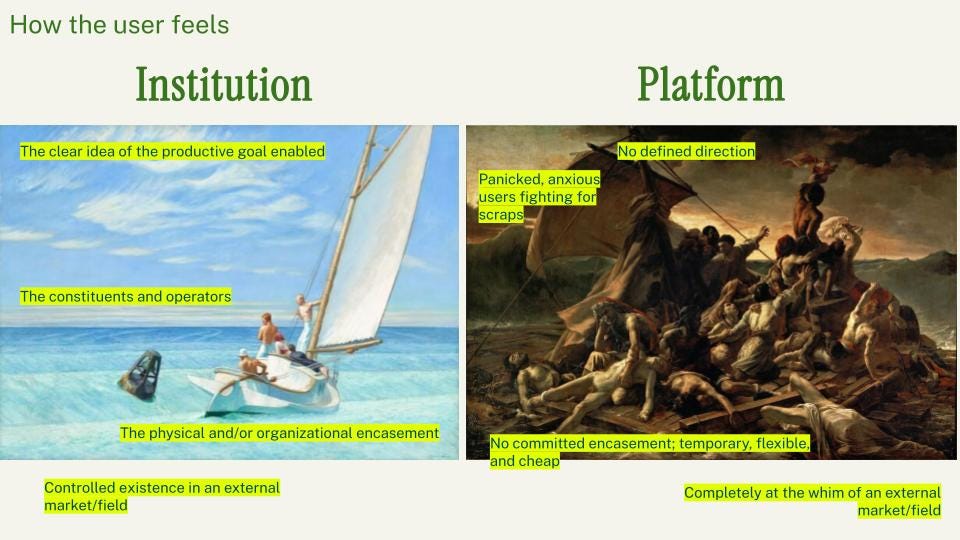

Now we get to the most difficult question. How do we define the institution? While the term itself has historically been a “floating signifier” and notoriously hard to define, the rise of platforms has thrown the essential characteristics of institutions into sharp relief. In the age of platforms, an institution can be understood as a complex and enduring organizational form distinct from the agile, often extractive, nature of digital platforms.

Institutions are a series of habits or practices, sometimes organized into a cohesive unit, that carry out the production of objects, expressions, or political goods and services. Institutions enact a mission, a conviction, or belief in spite of external influences that might compromise it. “Institutionalness” comes most into focus when we witness them persist in spite of a prevailing wisdom or opinion, not because they are unpopular or anti-democratic, but because they stand for something. That something — an idea, a good, or a norm — is reasonably fixed for the purpose of the constituents of the institution itself.2

Institutions are containers for things that are not problems to be solved. Institutions don’t define themselves by their delivery; instead they elevate the value of what results from their support above the speed and efficiency of their economic delivery. This doesn’t mean that everything they do will be right, just, or good. But it provides a ground upon which publics can encounter the production of these goods and services on their own terms.

Before I go further, a word of caution: I hope it is clear I am not here to lionize our institutions of the past. It is, in fact, their failures to deliver on their missions, their failure to adapt to the present, and their succumbing to the worst forces of elite capture. The institution is a symbol of many previous abusive edifices, and its very name almost arrives as a pejorative - to “institutionalize” is to sap the life from something - we shouldn’t design new institutions with their fixed power as the primary virtue. All of the institutional critique and the critical theory that began de-colonizing institutions was correct. It’s just that their solutions were no match for the digital age.

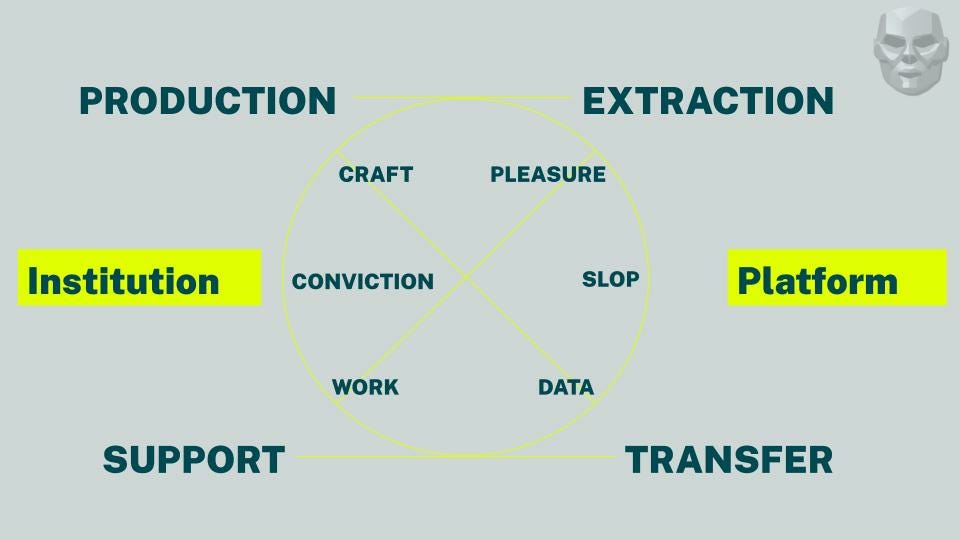

The simplest way to define the institutional form is by looking at what they produce in contrast to the form of the platform. Here are some examples of institutions and their platform replacements.

In each of these cases, the platform seeks not to deliver the material of the ecosystem but to colonize the transaction space to extract value.

The prime example of this is Spotify, who in 2017 began using fake AI generated music under their own on platform label to deliver music without paying for it. These so-called “Ghost Artists” have been uncovered thanks in part to Liz Pelly’s investigations. Spotify has refused to label the work as AI generated. They simply don’t care that the music is not real. They only care if transactions are taking place.

Platforms seek to replace institutions where value is most held in intangible, unquantifiable forms. Organizations that have missions tuned to something larger than themselves are the greatest foil for platforms. These “goods and services” of the institution cannot be replaced by the platform because not everything is a race for compute. And we are finding that out now.

In essence, the best institutions might act as “membranes” (a term I echo from the artist Jak Ritger), these membranes define what is let in, what is let out, and the energy produced. It is the keeper of the distinction between production and consumption - a distinction the platform collapses. Institutions embody the collective agreement and fabric of meaning that, above any external forces, builds, as opposed to extracts from, cultural and social value. In the age of platforms, the challenge is to reconfigure and revive institutions, employing “intra-institutional technology” that augments their missions without cannibalizing them, ensuring they remain resilient and essential brokers of human experience against the backdrop of ubiquitous computation and “AI slop”.

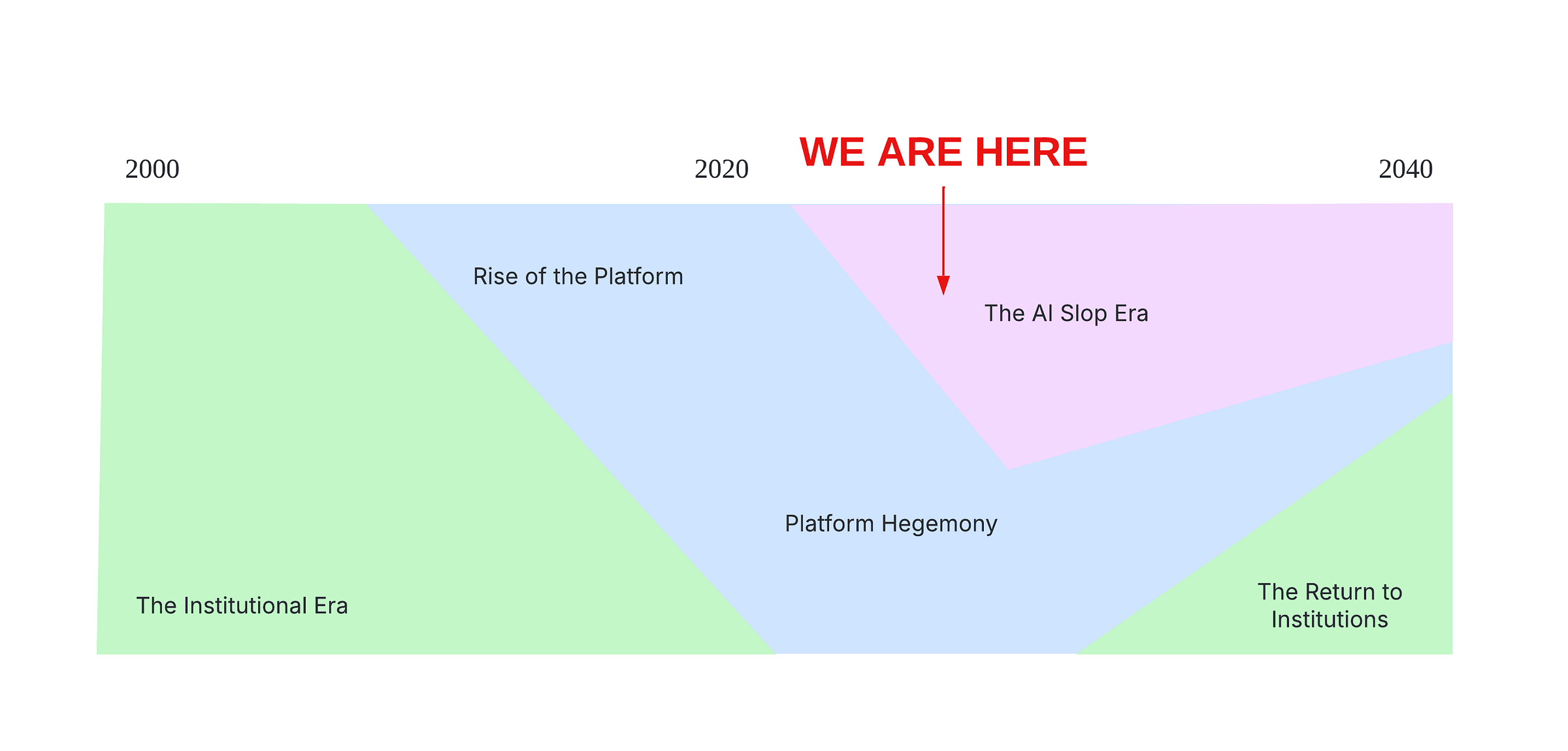

Here’s a rough speculative timeline for our new institutional project. Recall the Platform Era (2010 -2020). It was boom times for “free culture” and Zero interest rate subsidized cheap stuff and rented experiences. This was a large-scale transfer of previously un-digitized value in to the networks, and eventually centralized platforms, of the present. This surfeit of information and exchange paved the way - culturally and technically - for the AI era (2014 - present). Catapulted out of the AI winter by the advent of user friendly and functionally coherent Generative Adversarial Networks circa 2014, the focus of Silicon Valley’s intellectual and financial propaganda shifted rapidly. “Artificial intelligence” — which is itself a floating signifier for predictive or generative models of the world, and at worst, a marketing term for “machine learning”— has now moved into the territory of cultural and social institutions. Why? Well, because that is where the utopian needs to play.

Like every cycle of disruption, Silicon Valley must intervene and capture the social and cultural narrative from the non-digital meaning-making frameworks. It must reproduce this “meaning” through its proprietary software-as-a-service model. And it must do this all the while optimizing the outcomes for the managers of the computational platform and its owners.

What the platformists and the techno-determinists misunderstand is that driving automation costs to zero, and thus automating most “economic tasks”, will only reaffirm the importance and role of human institutions in constituting what is consumed and served. By making the economic concerns obsolete, it will remove the market’s authority in judging what is worth producing and worth consuming. The trick, then, is to re-situate institutional membranes in the new computational arrangement, where digital tools might liberate creativity but not to the unilateral gain of large, for-profit platforms incentivized only to grow.

While it may feel like we are on a one-way track towards this all-platform dystopia, be aware of the opposing flow:

With the platform era now coming to a close (partially due to AI slop’s overreach) and AI supposedly driving cognitive costs to zero, counterintuitively, our institutional structures will enter a growth phase in response to a new demand for shared narratives. Once we have retreated from the chaos of platform transactions, there will be a new premium put on human provenance, authenticity, and non-transactional connection. As AI slop fizzles out into its own endless machine loop, institutions take on newly essential brokering functions. What were once weaknesses in the transition to platforms become strengths.

What these coming institutions will look like and how they will sustain within digital frameworks is a question of political design, and less relevant to what digital tools are in place, provided they are not operated with the incentives of the platform.

With institutions, the material support for production is separated from its consumption, audience, and transmission. On the platforms, all of those need to be operating on the same rails to enable the totalizing optimization for the growth of the platform itself. On Substack, you are both paying for journalism and doing it at the same time - you are both audience and producer, cutting out the institutional middle man. When you discover music on spotify, you are not so much discovering music as you are discovering spotify, and in turn feeding the platform information they use to more optimally grow. This is because for both Spotify and Substack they are not measuring music or journalism, the institution, but measuring and growing their value from containing a monopoly on buyers and sellers of a formerly loosely entangled ecosystem. This is fundamentally different from the aim of journalism. Music and Journalism are just the pre-text. This disaggregated ecosystem of delivery and their central motivating ideal are simply the raw material for the platform. Without institutional fuel, the platform is just an unfulfilled potential network. Converting any shred of economic value or human joy into a two sided marketplace, tied up to protocols liable to manipulation and optimization, is the dream of the Venture Capital investor, not the engineer. The engineer can build and improve institutions without lapsing into the platform form. But they need organizational guardrails. We need a model to communicate the minimum viable requirements of an institution. I propose that you take a look at the sailboat.

1. Committed Organizational Encasement: Institutions possess a committed physical or organizational form, which can be diverse but is fundamentally synchronous. This encasement allows for the embodiment of an idea, mission, or responsibility for the production of a set of values.

The boat floats and moves, yet nonetheless has a committed structure and design.

2. Fixed Constituents and Operators: Institutions are composed of a clearly defined group of people who have a fixed relationship and roles within the institution. This clarity of roles and incentives is unlike the often ambiguous relationships found on platforms. On platforms, the operators (the users, the buyers, the sellers) are constantly pitted against one another in a war of all against all that is liable to instant optimization or change in order to benefit the growth of the platform itself. An institution’s operators tend to have structural bottlenecks to guard against suddenly changing the roles of constituents in ways that violate the organization’s larger purpose. E.g Uber is using drivers as a stop gap until autonomous vehicles arrive.

The boat has human operators that are bound in a structural commitment to sail.

3. Clear Productive Goal and Mission: Institutions are driven by a specific intent and a metaphysical idea of a productive goal or mission. This mission enacts a conviction or belief, often in spite of external influences, and dictates that what should be produced is intrinsically “worth consuming,” rather than merely providing the infrastructure for its consumption. Unlike platforms, which are content-agnostic and prioritize transmission or growth, institutions have a point of view on things in the world and an explicit future vision of what they will create.

The boat’s intent is to sail towards a destination.

4. Existence in an External Field and Responsibility to a Public: Institutions are not utopian, suspended monolithic spaces; they operate within an external field, facing demands and requiring compromises. They can even be sustained businesses that deal with markets, and they can take and hold power in ways that do seem to some as exploitative. Yet, crucially, they hold a greater responsibility to a public and always, a mission, aiming to serve a constituency in a broad, disinterested sense. They are subject to market logic, but not superseded by it.

The boat must adapt to wind and currents.

In contrast to this model of the institutional form is the platform, following this metaphor is something like the Medusa’s floating raft after a wreck.

No defined direction

Panicked, anxious users fighting for scraps

No committed encasement; it’s temporary, flexible, and cheap

Completely at the whim of an external market/field

To build anything today means succumbing to the immense pressure of working in the paradigm of the platform. So I’ll end with some more tactical contrasts to anyone wondering whether what they are building or designing is a platform, an institution, or something else along the spectrum.

1. Institutions have a Healthy Figure/Ground Relationship to Time. They have Good “Clock Speeds”

Here I call on Douglas Rushkoff’s use of the analogy of the innate relationship between Figure and Ground. In a traditional marketplace, the figures are the objects for sale; the money, on the other hand, is merely ground - literally the supportive infrastructural medium - the tool - that enables the flow of goods. It is the goods that are the central figure of the institution of the marketplace. He then speaks of the problem of figure ground inversion, a process by which a market becomes so financialized (like 21st century high speed financial trading, or digital platforms) where the ground ceases to be the simple infrastructural tools, and instead rises to become the central aim of the organism - the figure. In this inversion process the money becomes the primary Figure in the market, and the objects become merely the ground. This is all to say that good Institutions have a Figure/Ground relationship to time. Time is the ground, and the intent and missions are the figure.

When a platform creates asynchronous exchange - when many actors can work at any time without any kind of shared ordering or hierarchy - it achieves this at the expense of a shared narrative about the purpose of the exchange and the activity. Platforms put minimal effort into making this consideration, whereas institutions would never let the clock speed get too fast for the root activity that it supports. Where platforms are a mechanism for optimal delivery, Institutions are the clock themselves.

2. Supportive, Positive-Sum in Nature; Not extractive

Institutions are positive-sum producers, platforms are zero-sum extractors. They constitute the “raw” productive material of platforms. Institutions are extracted from, not extractive themselves. They organize themselves this way because they have a responsibility to something other than growth.

3. Institutions Must have a Specific Intent

Institutions have intent. They realize a mission that has a point of view on things in the world. Platforms care only about exchange in transfer - and they snuck in this side door of benevolent decentralization. As a result, platforms are deeply wary to try to paint a picture of what should be sent on their rails. An institution, on the contrary, should have an explicit future picture of what it will create.

4. Institutions Maintain Sustaining, not Accumulating, Funding Source

Every organization is influenced by the way it acquires and distributes resources to operate. Platforms accumulate the value of an investment. An institution’s funding sustains the enactment of the stated mission. The financial backing should come as close as possible to supporting the central mission, and not the growth of the mediating infrastructure.

5. Are Federalized and Reproductive, not Monopolistic

The platform’s optimal focus is exchange and transfer. They are designed to enact monopolistic control over these exchanges. Their designs do not account for competing platforms. The scale of software must realize its single purpose by bearing the infrastructure to anything in its path. Platforms don’t really believe in what they are making so much as they believe that they must be the means of mediation. It follows then that their only goal is to mediate more of the things, no matter what they are. Institutions, on the other hand, are fine with competitors. That’s just one more member in a community of shared narrative.

In the next several years we will be confronted with a disruptive collapse of existing institutions of various stripes. Though this time, the destruction will be directly and purposefully enacted by the agents of the platform installing AI and other extractive technologies into the administration of public life. Our answer to this assault cannot just be to make a new, different “improved” platform. We must reconfigure institutions for the age of ubiquitous computation.

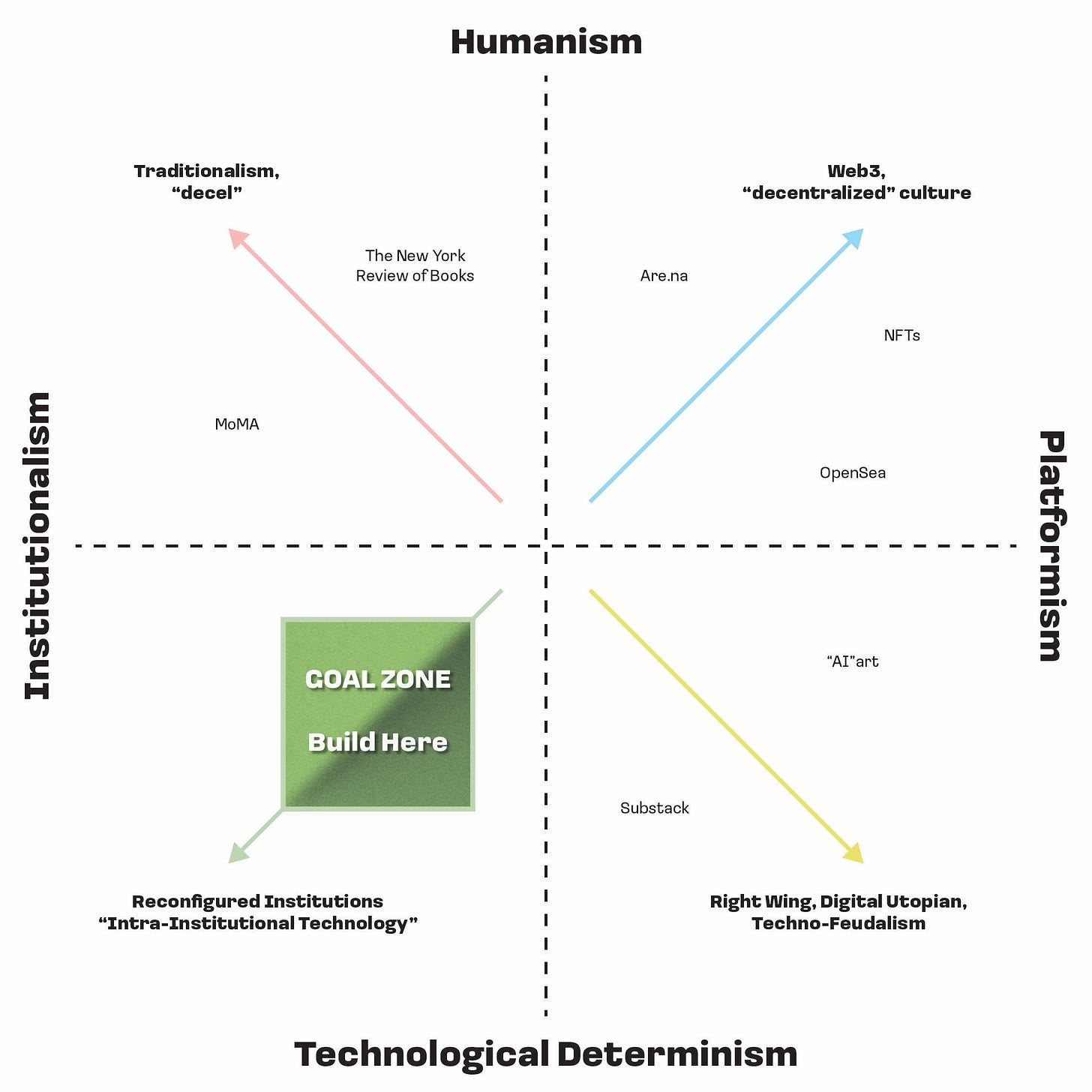

All of this exists on a spectrum. For example, these new institutions don’t need to be afraid of indulging in techno-determinism. They cannot, like the traditional institutions (in the upper left) ignore the technological change around them. A new type of organization must emerge - one that employs “intra-institutional” technology. The strongest of the democratic and/or intellectual qualities of institutions can still exist in their fullest expressions while being encased in, and elasticated by, software tools. The ideology underneath and within these new institutions will be a kind of enlightened techno-progressivism, defined as the idea that digital tools can augment the missions of institutions without cannibalizing them whole from the outside.

Intra-Institutional Technology is a call to build technology that’s not a “solution” to the problem of the humanist, democratic institution. It dispenses with the utopian visions of a cyberspace without political bodies, and does not aim to replace their functions with computation, as if that would make the problems simply disappear. Intra-institutional technology is hard. It does not take the techno-fix shortcuts. It has to design not just for the potential expressions of the underlying technology but for political and social constituents.

Some of what follows in this section was adapted from my work in The Guardian on the same topic.

I use a version of the introduction to this definition from my work with Do Not Research https://mikepepi.substack.com/cp/161848573

I'm having a hard time distinguishing the "new institutionalism" you're describing from just "current US-based nonprofit structures + technology." The mission-driven organization that attracts to it resources (philanthropic or revenue from services) and labor (for the "love" of it) exists. But, "go start a nonprofit" isn't all that appealing obviously. (Plus, it's just a hard as starting a commercial enterprise). Maybe what's needed is to get back into the nitty-gritty of post-2008 conversations about the range of options between C-Corp/pass-through entities and 501c3/4 operations. B-corps are about all there are now, and pretty weak. I recall talk about L3C structures about 15 years ago as a remedy for journalism. Where do entities like Craigslist or Wikipedia (even Reddit?) fall in your matrix?

Thanks for sharing this!

Is there any new institution you see emerging that matches the criteria you described at the end?